The Middle Class Mind

I was in Barcelona to attend a business conference. One evening, a small group of us found our way to a fancy bar with quiet music.

We knew each other - we’ve met all around the world, from developing-world resorts to New York City cafes. Our conversations are mostly stories and laughs with like minds. But in the middle of all the jokes, I got offended.

Someone in my group had said: “Nothing annoys me more than people who call themselves “entrepreneurs” while sitting around somewhere cheap like Chiang Mai and convincing themselves they’re living the dream.”

Everyone burst out in laughter and agreement. Definitely we weren’t those types. After all, our gin and tonics cost fifteen bucks.

Chalk it up to my palm tree pedigree, but for all the horrible things I’m willing to say and endure in conversation, this was the moment I got indignant.

Now, it’s easy to do what my friend had done - notice a small difference between your group and another, and then make a big deal of it. And yeah, it’s good for a joke. In my world, I hear cyclists criticise triathletes all the time. These are fellow endurance athletes who ride bikes, but - God pity their ignorant souls - also run and swim. Same goes for the war between vegans and Paleos - they savage each other and leave fatties like me to our ice cream.

And I’m guilty of it all the time. But that evening, I couldn't help but get pissed on behalf of broke-ass entrepreneurs. I can relate to them; I was one for a long time. And although being a broke-ass entrepreneur certainly doesn’t guarantee that you’ll become a wealthy one, I believe those who are willing to be broke - on purpose - are more likely to become rich.

One of comedian Adam Carolla's best bits is called "Rich Man, Poor Man." The idea is that the rich and poor share things that middle class people don’t. (For the sake of the bit, “poor” doesn’t refer to people who are struggling - it refers to those who’ve opted out of traditional employment and chosen a different lifestyle. Think of the guy who paints houses half the year so he can backpack the other half, or the Uber driver who works three days a week to fund his art project. Think of the #vanlife fisherman, or Fat Tony from Nassim Taleb’s books.)

Anyway, Carolla offers some shocking similarities between the lifestyles of the rich and the voluntary poor. Here are some of my favorites:

Drinks coffee and reads paper all afternoon on a Wednesday.

Spends all day in pajamas.

Owns a boat.

Hosts a wedding at their house.

Comfortable telling you how much money they earned last week.

Has backup cash under the bed (or equivalent).

Has five cars (for the voluntary poor, theirs are in the yard waiting to be rehabilitated and sold for profit).

More cleverly, there’s:

Has outdoor showers.

Sits at the top of the stadium…

It's a fun game, but we can think about it more seriously, too. What if there’s something that the rich and the voluntary poor both see - but the middle classes don’t? And, more seductively, what if there’s something about being broke that illuminates the path to wealth?

***

When I was a broke-ass middle-class kid, I thought about rich people through media images. (Cue Robin Leach voiceover.) After all, I didn’t meet many rich people. And when I occasionally did, they were gone just as quick as they came - off to wherever, while I was back to work.

Weirdly, I’d have met more rich people if I’d gone downscale. Go into a dive bar near a marina and strike up a conversation with a diesel engineer - you’ll learn a lot more about the wealthy than by hanging out with well-paid professionals who call themselves “Vice President.” Or, cut out the middleman and work for the rich directly - on their yachts, in their gardens, as a tutor to their children, or in hundred other ways.

Spending time around wealthy people (or the people who know them well) will teach you a lot about what being wealthy is like. But the same goes for living poor: by doing so, you might discover more about building wealth than you would by living high on the middle-class hog.

How? By beginning to claw your way out of the middle-class mindset that conflates income (or spending habits) with success. This is the whole point of baselining - to act on the idea that our time is more valuable than our money. I’ve spent a lot of time in Chiang Mai, and I can tell you that there are hundreds of entrepreneurs there who’ve had this exact insight - and are pursuing their dreams (including building successful businesses) because of it.

Of course, you don’t have to have a financial goal in mind. If you quit your job and head out somewhere cheap to explore your hobbies, your thoughts, and your world, you are living the dream. They even have a parable for that. In many tellings it’s called “The Fisherman and the Businessman.”

But once you have some success with your business, it’s easy to get snobby. My friend’s joke, back in that bar in Barcelona, depended on the in-group agreeing that we’re doing something right. We’re in the right cities. In the right industries. With the right business models. We all have high rents and expenses. “Responsibilities.” We laugh because those Chiang Mai kids are fooling themselves.

Except, of course, that none of us has it figured out either. In that Barcelona barroom, there wasn’t a single Mark Cuban or Elon Musk. We’re still seeking answers, too. But now we were using money and status symbols to prove something about our business prowess. It all felt a little too middle-class to laugh.

***

It also means that we’re blinding ourselves. We’ve had a little success, but what if that success is actually making it harder to achieve our next set of goals? What if it’s easier to go from the bottom to the top than from the middle to the top?

Let’s say you have fifteen thousand dollars to invest. You can choose between two entrepreneurs, both of whom have small service businesses. Your money buys you 20% of the company you select, and you only see that money again if that company sells for over $1M. So, your possible outcomes are either $200,000+ or nothing.

Here’s the catch: you only know one piece of information about each company - the location of its founder. One entrepreneur has lived in San Diego for fifteen years. The other sold house and moved to a small apartment in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Knowing only those two variables, where would you place your bet?

By now, you can probably guess where I’d put my money: on the entrepreneur in Vietnam. Because despite my buddy’s joke in the bar, being content to sit around somewhere cheap actually is a pretty decent strategy for becoming wealthy.

Of course you can’t just sit around. Self-made wealthy people are ambitious - without exception. But the sitting around part is valuable; it’s a way to clear your mind from all the things you’re “supposed” to do.

These “supposed-tos” dominate middle-class thinking: buying a decent car, getting a decent job, making decent money. They’re about appearing good enough. And they’re the kinds of pursuits that often stand in the way of getting wealthy.

“Sometimes I Wonder If I Should Go Back and Work for a Big Company”

A few nights after hearing my friend’s joke, I met a guy who was the butt of it.

He was piecing together a shaky income from a variety of sources. He was starting a family. He was nervous. His dream wasn’t working out as planned.

“All my friends from high school are further along than me. They’ve got homes, big paychecks, and nice lifestyles. I could have that too. I could go back, put my degree to use, and get a good job.”

By the standards of the digital entrepreneur crowd, this guy is doing okay - not great, but okay. But by the middle-class standards of everyone back home (or of the joker in the bar), he’s doing terribly. In fact, he’s doing so badly that he’s tempted to trade entrepreneurial stress (“What the hell am I doing?”) for a very different kind - the kind that comes with a steady paycheck.

This guy is fragile. And when you make fun of those who are “okay” with very small businesses on very small islands, you recreate the pressure that keeps so many people in ‘safe’ career paths. You tell them, “Do something that we perceive as successful, and do it right now. Look like us, or we won’t recognize you.”

That pressure sucks. It ruins people. And I’m committed to a romantic idea of what’s possible when you stay clear of all that.

But staying clear of it is tough. The middle class mind is handed to many of us in childhood, and it’s extremely difficult to shake.

Getting Poor to Get Rich as a Barbell Strategy

Nassim Taleb has a hundred cool insights about the world, and one of my favorites is his Barbell Strategy for investing. It works like this:

Cover all your downside: put yourself in ‘no lose’ situations most of the time. Then,

Expose yourself to many small investments that have the potential to win big. (For example, keep the majority of your money in cash (not the market) and live in a home you own 100%. Then invest 10% of your money in 10 highly volatile startups.)

You can take the same approach to your career. That’s baselining: saving some cash, living somewhere cheap, being frugal, and devoting all your waking energy to building assets. For those with an adventurous temperament, it’s a lot more fun than having a job. Better yet, I’ve seen it work many times. I’ve been writing this blog since 2009, and one of the things happening around me is that our readers are getting rich. These are not the people that you’d expect, either. They didn’t go to fancy colleges - and in some cases, didn’t go to college at all. They’re travelers and free spirits and computer nerds, people living out of their backpacks, showing up on random islands to talk about Google algorithms and VPN networks and website referrals. Often, society looks at these people as outsiders or failures - but now, they’re building wealth.

“Your Chances of Getting Rich Are Better If You’re Broke”

Felix Dennis, founder of Maxim magazine, delivers a similar message in his hilarious book How to Get Rich. He takes great pains to outline the difficulties of becoming wealthy [emphasis mine]:

Now you must leave the safety of the ant colony and the hive. You are to become a loner, an outcast, cut off from the very thing that defines what many of us believe we are. What is the first question usually asked by strangers of each other? Right, it’s “What do you do?” In some cultures, the way of answering may be different; but it nearly always relates to work in the West: “I’m a teacher; I’m in banking; I’m a dairy farmer;” … Our job defines us. But it cannot define you. Not anymore.

For Dennis, “being normal” and identifying with your job are risks. In fact, he argues that people with steady careers might as well give up on becoming wealthy. They have too much to lose. They have the middle class mind. What starts as a risk-management strategy - get a career! - ends up guaranteeing a lifetime of low-yield returns.

Risky!?

Even the Losers Get Lucky Sometimes

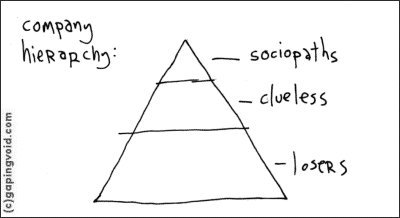

Venkat Rao reflected on the same phenomenon in The Gervais Principle, his brilliant analysis of career politics.

Check out the middle layer of the pyramid. This is where you’ll find people who call themselves “Senior Vice President of Marketing and Sales.” They really believe in the company, and they cheerlead and contribute. But they never quite make it to the top, because they don't break or build anything.

To paraphrase the author, those in the middle lack the competence or mindset to flow freely throughout the economy. They believe the company - and more broadly, their careers - will take care of them.

Look at the bottom layer, too: here you’ll find those who don’t feel any passion for the company; instead, they do the minimum necessary to avoid getting fired and perhaps do big things with their spare time. (Think of a competent, punctual, semi-bored programmer who listens to audiobooks all day long.) Occasionally - but only occasionally - these people get noticed and groomed for more powerful roles.

$1000 and a Backpack

In the early days of this blog, I often said that all I needed was “$1000 a month and a backpack.” Living at a low baseline appealed to me - and still does.

Lots of people lampooned the idea - and still do. But when I met Derek Sivers for the first time - a guy who built and sold CD Baby for $22M - the first thing he asked me was:

“Are you the $1000-a-month-and-a-backpack guy?”

“Yes,” I said, because I was.

And then he said something I’ll never forget.“

I love that idea.”

Thank you, Derek.

The Strange Identity of the Middle Class

Baselining. Using a barbell strategy to design your career. Valuing your time over money. There’s a pattern here.

In The Millionaire Fastlane, MJ DeMarco phrases it another way: he declares that “in order to become wealthy you need to produce more than you consume.”

Does this sound obvious? For a huge percentage of the middle-class, it isn’t. These people devote huge chunks of their lives to earning money, and then spend it on fancy gadgets to prove that the time spent earning it was worthwhile. At the same time, they’re sheepish about exactly how much they have, because they know that others have more.

The middle class mind is one that has come to identify with money. Those who have it can believe that the amount they earn says something important about who they are.

It’s easy to fall into this way of thinking, and hard to claw your way out.

So when our friends are working their tails off to change, let’s not make it any harder for them.

Instead, let’s give them a hand.

Cheers,

Dan

Like the TMBA? You can subscribe here.

Further reading: